Etel Adnan

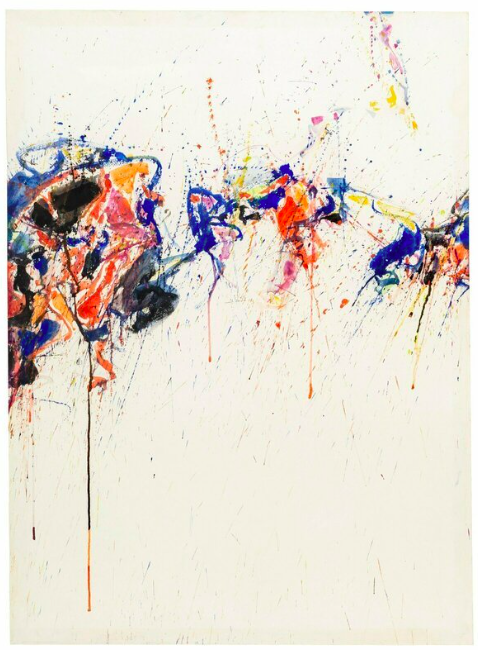

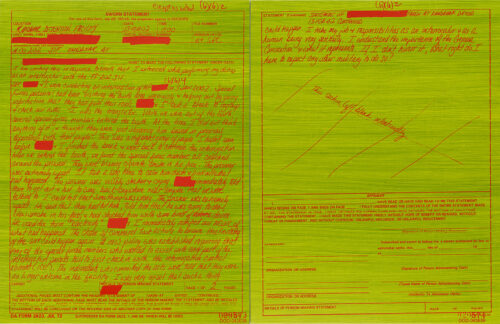

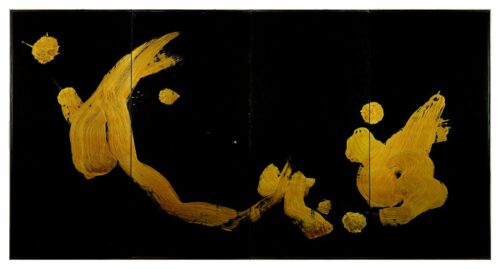

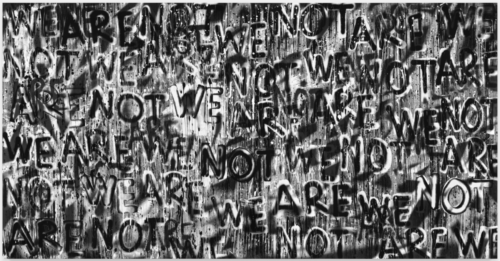

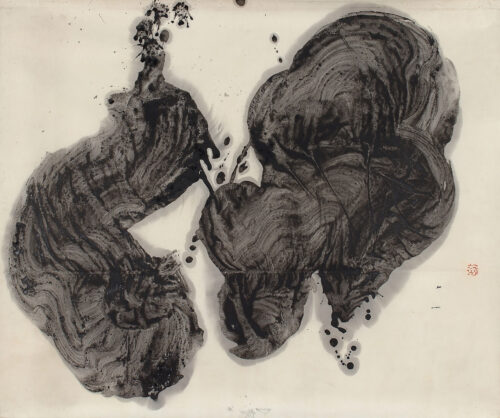

Etel Adnan’s visual works feature suns, moons and luminous colors. Her roots as a writer and artist are Lebanese; she grew up in Arab Beirut with Greek and Turkish as her first languages. Her poetry is clear and haunting; it is also political. The texts in her fold-outs stand for what can be said – but she anchors the written words in the inexpressible domain of bright colors. She studied at the Sorbonne, Berkeley and Harvard, which is why she writes in Arabic, French and English. For a long time she lived in Sausalito, California, where she also began to paint.

Etel Adnan (b. 1925 in Beirut, LB, d. 2021 in Paris, FR) grew up multilingually with Greek and Turkish as her native languages. She attended French schools in Beirut and began studying philosophy, continuing at the Sorbonne in Paris from 1949 and at the University of California Berkeley and Harvard University from 1955. From 1958, she taught philosophy at the Dominican College of California in San Rafael, meanwhile beginning her first art works: abstract drawings with pastels and landscape paintings. Adnan’s hallmark medium of expression became Leporellos, meter-long folding books originating from Japan, in which she combined poetry and painting, writing and drawing. In 1972, Etel Adnan met the artist Simone Fattal (b. 1942 in Damascus, Syria); from the 1980s onward, they lived together in California and France. As a writer and artist, the movement between different languages and cultures shaped Adnan’s lifework.

Her works have been shown at dOCUMENTA (13), Kassel (2012); the Whitney Biennial, New York (2014); and the 14th Istanbul Biennial (2015). Solo exhibitions have been held at the Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha (2014); the Museum der Moderne, Salzburg (2015); the Lenbachhaus, Munich (2022); and the K20 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Dusseldorf (2023).